2022-06-01 How fast are Linux pipes anyway?

In this post, we will explore how Unix pipes are implemented in Linux by iteratively optimizing a test program that writes and reads data through a pipe.1

We will begin with a simple program with a throughput of around 3.5GiB/s, and improve its performance twentyfold. The improvements will be informed by profiling the program using Linux’s perf tooling.2 The code is available on GitHub.

The post was inspired by reading a highly optimized FizzBuzz program, which pushes output to a pipe at a rate of ~35GiB/s on my laptop.3 Our first goal will be to match that speed, explaining every step as we go along. We’ll also add an additional performance-improving measure, which is not needed in FizzBuzz since the bottleneck is actually computing the output, not IO, at least on my machine.

We will proceed as follows:

- A first slow version of our pipe test bench;

- How pipes are implemented internally, and why writing and reading from them is slow;

- How the

vmspliceandsplicesyscalls let us get around some (but not all!) of the slowness; - A description of Linux paging, leading up to a faster version using huge pages;

- The final optimization, replacing polling with busy looping;

- Some closing thoughts.

Section 4 is the heaviest on Linux kernel internals, so it might be interesting even if you’re familiar with the other topics treated in the post. For readers not familiar with the topics treated, only basic knowledge of C is assumed.

Let’s begin!

The challenge, and a slow first version #

First of all, let’s start with measuring the performance of the fabled FizzBuzz program, following the rules laid down by the StackOverflow post:

% ./fizzbuzz | pv >/dev/null

422GiB 0:00:16 [36.2GiB/s]pv is “pipe viewer”, a handy utility to measure the throughput of data flowing through a pipe. So fizzbuzz is producing output at a rate of 36GiB/s.

fizzbuzz writes the output in blocks as big as the L2 cache, to strike a good balance between cheap access to memory and minimizing IO overhead.

On my machine, the L2 cache is 256KiB. Throughout this post, we’ll also output blocks of 256KiB, but without “computing” anything. Essentially, we’ll try to measure the upper bound for programs writing to a pipe with a reasonable buffer size.4

While fizzbuzz uses pv to measure speed, our setup will be slightly different: we’ll implement the programs on both ends of the pipe. This is so that we fully control the code involved in pushing and pulling data from the pipe.

The code is available in my pipes-speed-test repo. write.cpp implements the writing, and read.cpp the reading. write repeatedly writes the same 256KiB forever. read reads through 10GiB of data and terminates, printing the throughput in GiB/s. Both executables accept a variety of command line options to change their behavior.

The first attempt at reading and writing from pipes will be using the write and read syscalls, using the same buffer size as fizzbuzz. Here’s a view of the writing end:

int main() {

size_t buf_size = 1 << 18; // 256KiB

char* buf = (char*) malloc(buf_size);

memset((void*)buf, 'X', buf_size); // output Xs

while (true) {

size_t remaining = buf_size;

while (remaining > 0) {

// Keep invoking `write` until we've written the entirety

// of the buffer. Remember that write returns how much

// it could write into the destination -- in this case,

// our pipe.

ssize_t written = write(

STDOUT_FILENO, buf + (buf_size - remaining), remaining

);

remaining -= written;

}

}

}This snippet and following ones omit all error checking for brevity.5 The memset ensures that the output will be printable, but also plays another role, as we’ll discuss later.

The work is all done by the write call, the rest is making sure that the whole buffer is written. The read end is very similar, but reading data into buf, and terminating when enough has been read.

After building, the code from the repo can be run as follows:

% ./write | ./read

3.7GiB/s, 256KiB buffer, 40960 iterations (10GiB piped)We’re writing the same 256KiB buffer filled with 'X's 40960 times, and measuring the throughput. What’s worrying is that we’re 10 times slower than fizzbuzz! And we’re not doing any work, just writing bytes to the pipe.

It turns out that we can’t get much faster than this by using write and read.

The trouble with write #

To find out what our program is spending time on, we can use perf:6 7

% perf record -g sh -c './write | ./read'

3.2GiB/s, 256KiB buffer, 40960 iterations (10GiB piped)

[ perf record: Woken up 6 times to write data ]

[ perf record: Captured and wrote 2.851 MB perf.data (21201 samples) ]The -g instructs perf to record call graphs: this will allow us to take a top-down look at where time is being spent.

We can take a look at where time is spent using perf report. Here is a lightly redacted excerpt, breaking down where write spends its time:8

% perf report -g --symbol-filter=write

- 48.05% 0.05% write libc-2.33.so [.] __GI___libc_write

- 48.04% __GI___libc_write

- 47.69% entry_SYSCALL_64_after_hwframe

- do_syscall_64

- 47.54% ksys_write

- 47.40% vfs_write

- 47.23% new_sync_write

- pipe_write

+ 24.08% copy_page_from_iter

+ 11.76% __alloc_pages

+ 4.32% schedule

+ 2.98% __wake_up_common_lock

0.95% _raw_spin_lock_irq

0.74% alloc_pages

0.66% prepare_to_wait_event

47% of the time is spent in pipe_write, which is what write resolves to if we’re writing to a pipe. This is not surprising — we’re spending roughly half of the time writing, and the other half reading.

Within pipe_write, 3/4 of the time is spent copying or allocating pages (copy_page_from_iter and __alloc_pages). If we already have an idea of how communication between the kernel and userspace works this might make some sense. Regardless, to fully understand what’s happening we must first understand how pipes work.

What are pipes made of? #

The data structure holding a pipe can be found in include/linux/pipe_fs_i.h, and the operations on it in fs/pipe.c.

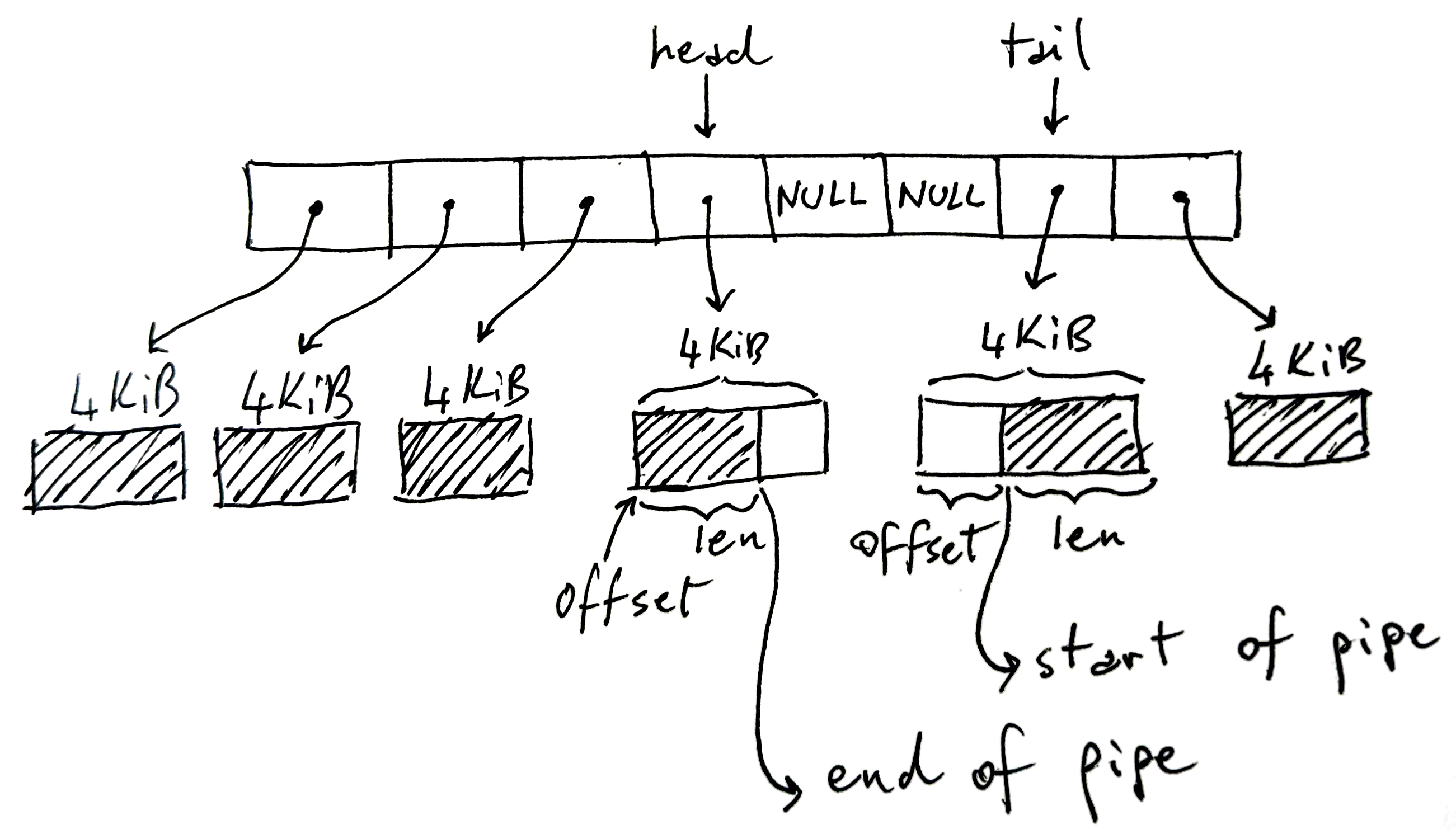

A Linux pipe is a ring buffer holding references to pages where the data is written to and read from:

In the image above the ring buffer has 8 slots, but we might have more or less, the default being 16. Each page is 4KiB on x86-64, but might be of different sizes on other architectures. In total, this pipe can hold at most 32KiB of data. This is a key point: every pipe has an upper bound on the total amount of data it can hold before it’s full.

The shaded part of the diagram represents the current pipe data, the non-shaded part the empty space in the pipe.

Somewhat counterintuitively, head stores the write-end of the pipe. That is, writers will write into the buffer pointed at by head, and increase head accordingly if they need to move onto the next buffer. Within the write buffer, len stores how much we’ve written in it.

Conversely, tail stores the read-end of the pipe: readers will start consuming the pipe from there. offset indicates where to start reading from.

Note that tail can appear after head, like in the picture, since we’re working with a circular/ring buffer. Also note that some slots might be unused when we haven’t filled the pipe completely — the NULL cells in the middle. If the pipe is full (no NULLs and no free space in the pages), write will block. If the pipe is empty (all NULLs), read will block.

Here’s an abridged version of the C data structures in pipe_fs_i.h:

struct pipe_inode_info {

unsigned int head;

unsigned int tail;

struct pipe_buffer *bufs;

};

struct pipe_buffer {

struct page *page;

unsigned int offset, len;

};We’re omitting many fields here, and we’re not explainining what struct page contains yet, but this is the key data structure to understanding how reading and writing from a pipe happens.

Reading and writing to pipes #

Let’s now go to the definition of pipe_write, to try and make sense of the perf output shown before.

Here is a simplified explanation of how pipe_write works:

- If the pipe is already full, wait for space and restart;

- If the buffer currently pointed at by

headhas space, fill that space first; - While there’s free slots, and there are remaining bytes to write, allocate new pages and fill them, updating

head.

The operations described above are protected by a lock, which pipe_write acquires and releases as necessary.

pipe_read is the mirror image of pipe_write, except that we consume pages, free them when we’ve fully read them, and update tail.9

So, we now have a quite unpleasant picture of what is going on:

- We copy each page twice, once from user memory to the kernel, and back again from the kernel to user memory;

- The copying is done one 4KiB page at a time, interspersed with other activity, such as the synchronization between read and write, and page allocation and freeing;

- We are working with memory that might not be contiguous, since we’re constantly allocating new pages;

- We’re acquiring and releasing the pipe lock.

On this machine, sequential RAM reading clocks at around 16GiB/s:

% sysbench memory --memory-block-size=1G --memory-oper=read --threads=1 run

...

102400.00 MiB transferred (15921.22 MiB/sec)Given all the fiddliness listed above, a 4x slowdown compared to single-threaded sequential RAM speed is not that surprising.

Tweaking the buffer size or the pipe size to reduce the amount of syscall and synchronization overhead, or tuning other parameters will not get us very far. Luckily, there is a way to get around the slowness of write and of read altogether.

Splicing to the rescue #

This copying of buffers from user memory to the kernel and back is a frequent thorn in the side of people needing to do fast IO. One common solution is to just cut the kernel out of the picture and perform IO operations directly. For example we might interact directly with a network card and bypass the kernel for low-latency networking.

In general when we write to a socket, or a file, or in our case a pipe, we’re first writing to a buffer somewhere in the kernel, and then let the kernel do its work. In the case of pipes, the pipe is a series of buffers in the kernel. All this copying is undesirable if we’re in the business of performance.

Luckily, Linux includes system calls to speed things up when we want to move data to and from pipes, without copying. Specifically:

splicemoves data from a pipe to a file descriptor, and vice-versa.vmsplicemoves data from user memory into a pipe.10

Crucially, both operations work without copying anything.

Now that we know how pipes work, we can already vaguely imagine how the two operations function: they just “grab” an existing buffer from somewhere and put it into the pipe ring buffer, or the reverse, rather than allocating new pages as needed:

We’ll soon see exactly how this works.

Splicing in practice #

Let’s replace write with vmsplice. This is the signature for vmsplice:

struct iovec {

void *iov_base; // Starting address

size_t iov_len; // Number of bytes

};

// Returns how much we've spliced into the pipe

ssize_t vmsplice(

int fd, const struct iovec *iov, size_t nr_segs, unsigned int flags

);fd is the target pipe, struct iovec *iov is an array of buffers we’ll be moving to the pipe. Note that vmsplice returns how much was “spliced” into the pipe, which might not be the full amount, much like how write returns how much was written. Remember that pipes are bounded by how many slots they have in the ring buffer, and vmsplice is not exempt from this restriction.

We also need to be a bit careful when using vmsplice. Since the user memory is moved to the pipe without copying, we must ensure that the read-end consumes it before we can reuse the spliced buffer.

For this reason fizzbuzz uses a double buffering scheme, which works as follows:

- Split the 256KiB buffer in two;

- Set the pipe size to 128KiB, this will have the effect of setting the pipe ring buffer to have 128KiB/4KiB = 32 slots;

- Alternate between writing to the first half-buffer and using

vmspliceto move it to the pipe and doing the same with the other half.

The fact that the pipe size is set to 128KiB, and that we wait for vmsplice to fully output one 128KiB buffer, ensures that by the time we’re done with one iteration of vmsplice we know that the the previous buffer has been fully read — otherwise we would not have been able to fully vmsplice the new 128KiB buffer into the 128KiB pipe.

Now, we’re not actually writing anything to the buffers, but we’ll keep the double buffering scheme since a similar scheme would be required for any program actually writing content.11

Our write loop now looks something like this:

int main() {

size_t buf_size = 1 << 18; // 256KiB

char* buf = malloc(buf_size);

memset((void*)buf, 'X', buf_size); // output Xs

char* bufs[2] = { buf, buf + buf_size/2 };

int buf_ix = 0;

// Flip between the two buffers, splicing until we're done.

while (true) {

struct iovec bufvec = {

.iov_base = bufs[buf_ix],

.iov_len = buf_size/2

};

buf_ix = (buf_ix + 1) % 2;

while (bufvec.iov_len > 0) {

ssize_t ret = vmsplice(STDOUT_FILENO, &bufvec, 1, 0);

bufvec.iov_base = (void*) (((char*) bufvec.iov_base) + ret);

bufvec.iov_len -= ret;

}

}

}Here are the results writing with vmsplice, rather than write:

% ./write --write_with_vmsplice | ./read

12.7GiB/s, 256KiB buffer, 40960 iterations (10GiB piped)This reduces by half the amount of copying we need to do, and already improves our througput more than threefold — to 12.7GiB/s. Changing the read end to use splice, we eliminate all copying, and get another 2.5x speedup:

% ./write --write_with_vmsplice | ./read --read_with_splice

32.8GiB/s, 256KiB buffer, 40960 iterations (10GiB piped)Fishing for pages #

What next? Let’s ask perf:

% perf record -g sh -c './write --write_with_vmsplice | ./read --read_with_splice'

33.4GiB/s, 256KiB buffer, 40960 iterations (10GiB piped)

[ perf record: Woken up 1 times to write data ]

[ perf record: Captured and wrote 0.305 MB perf.data (2413 samples) ]

% perf report --symbol-filter=vmsplice

- 49.59% 0.38% write libc-2.33.so [.] vmsplice

- 49.46% vmsplice

- 45.17% entry_SYSCALL_64_after_hwframe

- do_syscall_64

- 44.30% __do_sys_vmsplice

+ 17.88% iov_iter_get_pages

+ 16.57% __mutex_lock.constprop.0

3.89% add_to_pipe

1.17% iov_iter_advance

0.82% mutex_unlock

0.75% pipe_lock

2.01% __entry_text_start

1.45% syscall_return_via_sysretThe lion’s share of the time is taken by locking the pipe for writing (__mutex_lock.constprop.0), and by moving the pages into the pipe (iov_iter_get_pages). There isn’t so much we can do about the locking, but we can improve the performance of iov_iter_get_pages.

As the name suggests, iov_iter_get_pages turns the struct iovecs we feed into vmsplice into struct pages to put into the pipe. To understand what this function actually does, and how to speed it up, we must first take a detour into how the CPU and Linux organize pages.

A whirlwind tour of paging #

As you might be aware of, processes do not refer to locations in RAM directly: instead, the are assigned virtual memory addresses, which get resolved to physical addresses. This abstraction is known as virtual memory, and has all sorts of advantages we won’t cover here — the most obvious being that it significantly simplifies running multiple processes competing for the same physical memory.

In any case, whenever we execute a program and we load/store from/to memory, the CPU needs to convert our virtual address to a physical address. Storing a mapping from every virtual address to every corresponding physical address would be impratical. Therefore memory is split up in uniformly sized chunks, called pages, and virtual pages are mapped to physical pages:12

There’s nothing special about 4KiB: each architecture picks a size, based on various tradeoffs — some of which we’ll soon explore.

To make this a bit more precise, let’s imagine allocating 10000 bytes using malloc:

void* buf = malloc(10000);

printf("%p\n", buf); // 0x6f42430As we use them, our 10k bytes will look contiguous in virtual memory, but will be mapped to 3 not necessarily contiguous physical pages:13

One of the tasks of the kernel is to manage this mapping, which is embodied in a data structure called the page table. The CPU specifies how the page table looks (since it needs to understand it), and the kernel manipulates it as needed. On x86-64 the page table is a 4-level, 512-way tree, which itself lives in memory.14 Each node of this tree is (you guessed it!) 4KiB wide, with each entry within the node leading to the next level being 8 bytes (4KiB/8bytes = 512). The entries contain the address of the next node, along with other metadata.

We have one page table per process — or in other words, each process has a reserved virtual address space. When the kernel context-switches to a process, it sets the special register CR3 to the physical address of the root of this tree.15 Then whenever a virtual address needs to be converted to a physical address, the CPU splits up the address in sections, and uses them to walk this tree and compute the physical address.

To make these concepts less abstract, here’s a visual depiction of how the virtual address 0x0000f2705af953c0 might be resolved to a physical address:

The search starts from the first level, called the “page global directory”, or PGD, the physical location of which is stored in CR3. The first 16 bits of the address are unused.16 We use the next 9 bits the PGD entry, and traverse down to the second level, “page upper directory”, or PUD. The next 9 bits are used to select an entry from the PUD. The process repeats for the next two levels, PMD (“page middle directory”), and PTE (“page table entry”). The PTE tells where the actual physical page we’re looking for is, and then we use the last 12 bits to find the offset inside the page.

The sparse structure of the page table allows the mapping to be gradually built up as new pages are needed. Whenever a process needs memory, the page table will be updated with a new entry by the kernel.

The role of struct page #

The struct page data structure is a key piece of this machinery: it is what the kernel uses to refer to a single physical page, storing its physical address and all sorts of other metadata about it.17 For instance we can get a struct page from the information contained in the PTE (the last level of the page table described above). In general it is used pervasively in all code handling page-related matters.

In the case of pipes, struct page is used to hold their data in the ring buffer, as we’re already seen:

struct pipe_inode_info {

unsigned int head;

unsigned int tail;

struct pipe_buffer *bufs;

};

struct pipe_buffer {

struct page *page;

unsigned int offset, len;

};However, vmsplice accepts virtual memory as input, while struct page refers to physical memory directly.

Therefore we need turn arbitrary chunks of virtual memory into a bunch of struct pages. This is exactly what iov_iter_get_pages does, and where we’re spending half of our time:

ssize_t iov_iter_get_pages(

struct iov_iter *i, // input: a sized buffer in virtual memory

struct page **pages, // output: the list of pages which back the input buffers

size_t maxsize, // maximum number of bytes to get

unsigned maxpages, // maximum number of pages to get

size_t *start // offset into first page, if the input buffer wasn't page-aligned

);struct iov_iter is a Linux kernel data structure representing various ways of walking through chunks of memory, including struct iovec. In our case, it will point to a 128KiB buffer. vmsplice will use iov_iter_get_pages to turn the input buffer into a bunch of struct pages, and hold on to them. Now that you know how paging works, you might vaguely imagine how iov_iter_get_pages works as well, but we’ll explain it in detail in the next section.

We’ve rapidly gone through a lot of new concepts, so to recap:

- Modern CPUs use virtual memory for their processes;

- Memory is organized in regularly-sized pages;

- The CPU translates virtual addresses into physical addresses using a page table mapping virtual pages to physical pages;

- The kernel adds and removes entries to the page table as necessary;

- Pipes are made out of references to physical pages, so

vmsplicemust convert virtual memory ranges into physical pages, and hold on to them.

The cost of getting pages #

The time spent in iov_iter_get_pages is really entirely spent in another function, get_user_pages_fast:

% perf report -g --symbol-filter=iov_iter_get_pages

- 17.08% 0.17% write [kernel.kallsyms] [k] iov_iter_get_pages

- 16.91% iov_iter_get_pages

- 16.88% internal_get_user_pages_fast

11.22% try_grab_compound_head

get_user_pages_fast is a more bare-bones version of iov_iter_get_pages:

int get_user_pages_fast(

// virtual address, page aligned

unsigned long start,

// number of pages to retrieve

int nr_pages,

// flags, the meaning of which we won't get into

unsigned int gup_flags,

// output physical pages

struct page **pages

)Here “user” (as opposed to “kernel”) refers to the fact that we’re turning virtual pages into references to physical pages.

To get our struct pages, get_user_pages_fast does exactly what the CPU would do, but in software: it walks the page table to collect all the physical pages, storing the results in struct pages. In our case, we have a 128KiB buffer, and 4KiB pages, so we’ll have nr_pages = 32.18 get_user_pages_fast will need to walk the page table tree collecting 32 leaves, and storing the result in 32 struct pages.

get_user_pages_fast also needs to make sure that the physical page is not repurposed until the caller doesn’t need it anymore. This is achieved in the kernel using a reference count stored in struct page, which is used to know when a physical page can be released and repurposed in the future. The caller of get_user_pages_fast must, at some point, release the pages again with put_page, which will decrease the reference count.

Finally, get_user_pages_fast behaves differently depending on whether virtual addresses are already in the page table. This is where the _fast suffix comes from: the kernel will first try to get an already existing page table entry and corresponding struct page by just walking the page table, which is relatively cheap, and fall back to producing a struct page by other, more expensive means otherwise. The fact that we memset the memory at the beginning will ensure that we never end up in the “slow” path of get_user_pages_fast, since the page table entries will be created as our buffer is filled with 'X's.19

Note that the get_user_pages family of functions is not only useful for pipes — in fact, it is central in many drivers. A typical use is related to the kernel bypass we mentioned: a driver for a network card might use it to turn some user memory region into a physical page, then communicate the physical page location to the network card, and have the network card interact directly with that memory region without kernel involvement.

Huge pages #

Up to now we’ve presented pages as always being of the same size — 4KiB on x86-64. However, many CPU architectures, including x86-64, include larger page sizes. In the case of x86-64, we not only have 4KiB pages (the “standard” size), but also 2MiB and even 1GiB pages (“huge” pages). In the rest of the post we’ll only deal with 2MiB huge pages, since 1GiB pages are fairly uncommon, and overkill for our task anyway.

| Architecture | Smallest page size | Larger page sizes |

|---|---|---|

| x86 | 4KiB | 2MiB, 4MiB |

| x86-64 | 4KiB | 2MiB, 1GiB20 |

| ARMv7 | 4KiB | 64KiB, 1MiB, 16MiB |

| ARMv8 | 4KiB | 16KiB, 64KiB |

| RISCV32 | 4KiB | 4MiB |

| RISCV64 | 4KiB | 2MiB, 1GiB, 512GiB, 256 TiB |

| Power ISA | 8KiB | 64 KiB, 16 MiB, 16 GiB |

Page sizes available on architectures commonly used today, from Wikipedia.

The main advantage of huge pages is that bookkeeping is cheaper, since there’s fewer of them needed to cover the same amount of memory. Moreover other operations are cheaper too, such as resolving a virtual address to a physical address, since one level less of page table is needed: instead of having a 12-bit offset into the page, we’ll have a 21-bit offset, and one less page table level.

This relieves pressure on the parts of the CPUs that handle this conversion, leading to performance improvements in many circumstances.21 However, in our case, the pressure is not on the hardware that walks the page table, but on its software counterpart which runs in the kernel.

On Linux, we can allocate a 2MiB huge page in a variety of ways, such as by allocating memory aligned to 2MiB and then using madvise to tell the kernel to use huge pages for the provided buffer:

void* buf = aligned_alloc(1 << 21, size);

madvise(buf, size, MADV_HUGEPAGE)Switching to huge pages in our program yields another ~50% improvement:

% ./write --write_with_vmsplice --huge_page | ./read --read_with_splice

51.0GiB/s, 256KiB buffer, 40960 iterations (10GiB piped)However, the reason for the improvements is not totally obvious. Naively, we might think that by using huge pages struct page will just refer to a 2MiB page, rather than 4KiB.

Sadly this is not the case: the kernel code assumes everywhere that a struct page refers to a page of the “standard” size for the current architecture. The way this works for huge pages (and in general for what Linux calls “compound pages”) is that a “head” struct page contains the actual information about the backing physical page, with successive “tail” pages just containing a pointer to the head page.

So to represent 2MiB huge page we’ll have 1 “head” struct page, and up to 511 “tail” struct pages. Or in the case of our 128KiB buffer, 31 tail struct pages:22

Even if we need all these struct pages, the code generating it ends up significantly faster. Instead of traversing the page table multiple times, once the first entry is found, the following struct pages can be generated in a simple loop. Hence the performance improvement!

Busy looping #

We’re almost done, I promise! Let’s look at perf output once again:

- 46.91% 0.38% write libc-2.33.so [.] vmsplice

- 46.84% vmsplice

- 43.15% entry_SYSCALL_64_after_hwframe

- do_syscall_64

- 41.80% __do_sys_vmsplice

+ 14.90% wait_for_space

+ 8.27% __wake_up_common_lock

4.40% add_to_pipe

+ 4.24% iov_iter_get_pages

+ 3.92% __mutex_lock.constprop.0

1.81% iov_iter_advance

+ 0.55% import_iovec

+ 0.76% syscall_exit_to_user_mode

1.54% syscall_return_via_sysret

1.49% __entry_text_start

We’re now spending a significant amount of time waiting for the pipe to be writeable (wait_for_space), and waking up readers which were waiting for the pipe to have content (__wake_up_common_lock).

To sidestep these synchronization costs, we can ask vmsplice to return if the pipe cannot be written to, and busy loop until it is — and the same when reading with splice:

...

// SPLICE_F_NONBLOCK will cause `vmsplice` to return immediately

// if we can't write to the pipe, returning EAGAIN

ssize_t ret = vmsplice(STDOUT_FILENO, &bufvec, 1, SPLICE_F_NONBLOCK);

if (ret < 0 && errno == EAGAIN) {

continue; // busy loop if not ready to write

}

...By busy looping we get another 25% performance increase:

% ./write --write_with_vmsplice --huge_page --busy_loop | ./read --read_with_splice --busy_loop

62.5GiB/s, 256KiB buffer, 40960 iterations (10GiB piped)Obviously busy looping comes at the cost of fully occupying a CPU core waiting for vmsplice to be ready. But often this compromise is worth it, and in fact it is a common pattern for high-performance server applications: we trade off possibly wasteful CPU utilization for better latency and/or throughput.

In our case, this concludes our optimization journey for our little synthetic benchmark, from 3.5GiB/s to 65GiB/s.

Closing thoughts #

We’ve systematically improved the performance of our program by looking at the perf output and the Linux source. Pipes and splicing in particular aren’t really hot topics when it comes to high-performance programming, but the themes we’ve touched upon are: zero-copy operations, ring buffers, paging & virtual memory, synchronization overhead.

There are some details and interesting topics I left out, but this blog post was already spiraling out of control and becoming too long:

In the actual code, the buffers are allocated separatedly, to reduce page table contention by placing them in different page table entries (something that the FizzBuzz program also does).

Remember that when a page table entry is taken with

get_user_pages, its refcount is increased, and decreased onput_page. If we use two page table entries for the two buffers, rather than one page table entry for both of them, we have less contention when modifying the refcount.The tests are ran by pinning the

./writeand./readprocesses to two cores withtaskset.The code in the repo contains many other options I played with, but did not end up talking about since they were irrelevant or not interesting enough.

The repo also contains a synthetic benchmark for

get_user_pages_fast, which can be used to measure exactly how much slower it runs with or without huge pages.Splicing in general is a slightly dubious/dangerous concept, which continues to annoy to kernel developers.

Please let me know if this post was helpful, interesting, or unclear!

Acknowledgements #

Many thanks to Alexandru Scvorţov, Max Staudt, Alex Appetiti, Alex Sayers, Stephen Lavelle, Peter Cawley, and Niklas Hambüchen for reviewing drafts of this post. Max Staudt also helped me understand some subtleties of get_user_pages.